A well-known math professor once said, "Mathematics is food for the brain." And, at the National Museum of Mathematics (also known as MoMath) in New York City, the aim is to keep your brain well fed in the context of fun. MoMath CEO and executive director Cindy Lawrence talks about this innovative institution’s history, exhibits, and perception-changing goals—all of which add up to make it the coolest thing to ever happen to math.

How did it all begin with MoMath?

There was a small math museum on Long Island that had shut down. A mathematician named Glen Whitney was dismayed to hear this, so he came up with the idea to open a larger-scale museum of math. But when we started telling people about it, people assumed nobody would come.

We had a little bit of money to get started, so we built a traveling math exhibit, which made its debut in June 2009. It quickly became popular, especially with math teachers. This proved that having a math museum was a good idea, and we ended up raising about $23 million to open a permanent location. What was originally imagined as a 5,000-square-foot museum in the suburbs of New York became a 19,000-square-foot facility off Broadway.

Why do you think it is so important for people to have an interest in math?

At its core, math is about logic and problem-solving—much like life. Learning to be a critical thinker is extremely important. There’s also a beauty in the “aha!” moment that’s similar to how an artwork or a piece of music can be beautiful.

How does MoMath pique such interest?

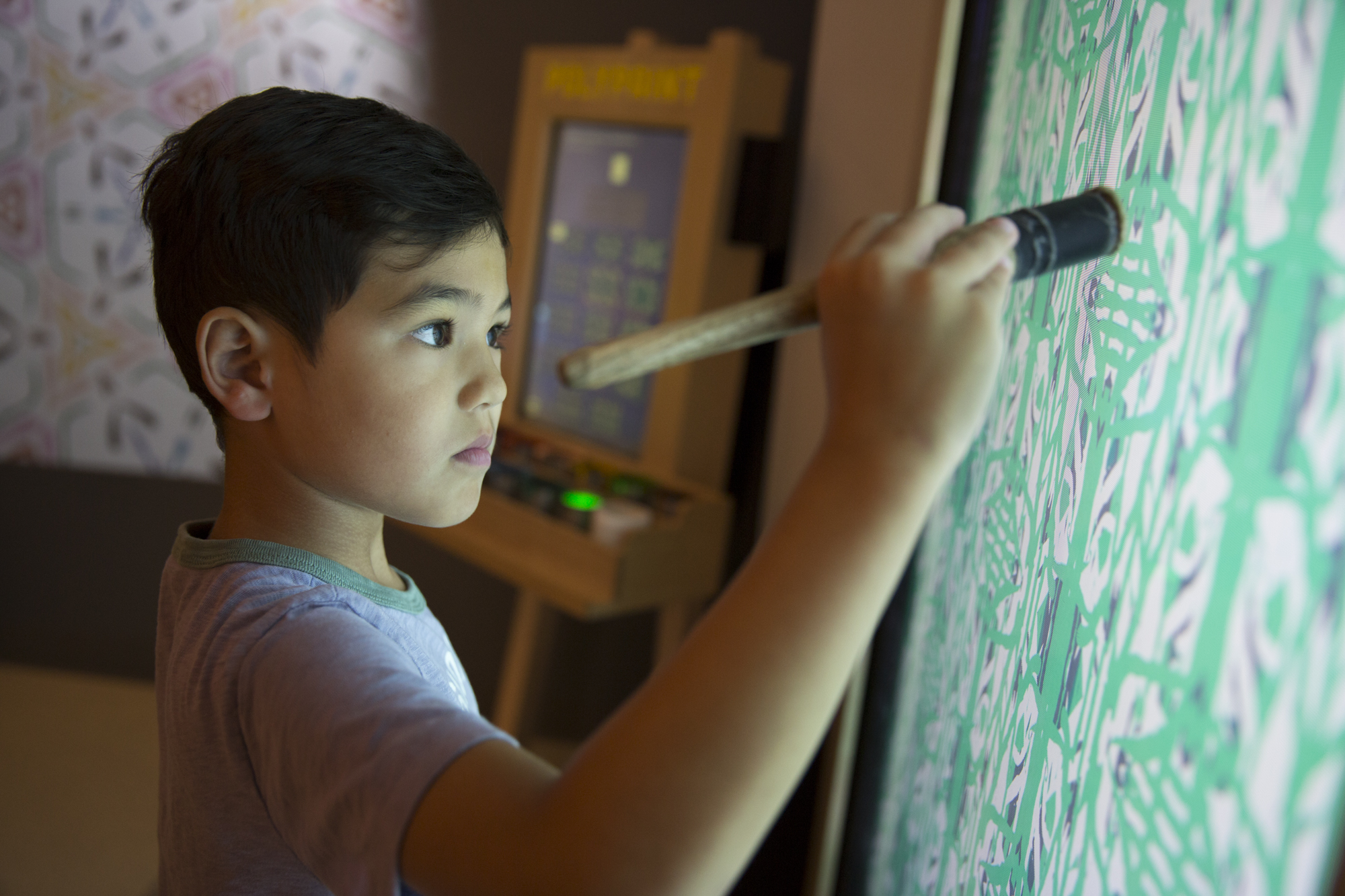

When people hear the phrase “math museum,” they envision that there will be calculators, rulers, graph paper, and mathematical symbols, and that's not the case. When you walk in, you see a world of strange but beautiful objects, including our most popular exhibit, a functional, adult-sized tricycle with square wheels. The museum is a very hands-on, immersive, physical, full-body environment for all ages.

What are some of the other popular exhibits at MoMath?

One of our most popular exhibits is a basketball exhibit called Hoop Curves. You take a free throw and a camera system records the height at which the ball was launched, the speed, and the angle, and whether the shot went in.

The latest is called Synchronized Spin, which features works created by a brilliant artist and inventor named John Edmark. When you spin these sculptures very quickly and put them under a strobe light, they seem to be growing or shrinking. These can be enjoyed just for the art, but if you take a moment to understand what’s going on, it’s a very simple math series that underlies his art, which we see in nature—like the pattern of growth in a pine cone or inside of a sunflower. It’s quite compelling, and people are really enjoying the exhibit.

What does your free public presentation series, Math Encounters, add to the MoMath experience?

Math Encounters came out of a need to have a meeting place for like-minded math enthusiasts. For almost ten years, it has served as a gathering place to enjoy hands-on math presentations. We’ve been very successful in finding engaging research-level mathematicians for the lectures, which have spanned all kinds of interesting areas in which you’d never think math would be involved. We've had Math Encounters on math and dance, math and art, math and music, and math and magic. In one of our latest Math Encounters, a mathematician, Penny Haxell, discusses math for the cruise director, exploring how to maximize groupings for social events and so forth.

How does MoMath celebrate Pi Day (March 14)?

We always do something on Pi Day, but in 2020 it’s being celebrated as the first-ever UNESCO International Day of Mathematics, and we’re the New York partner for UNESCO. We’re excited to be part of that worldwide event.

Our main feature is a giant Hula-Hoop contest. A lot of people know pi as an interesting number (3.14…) that goes on and on and never ends, but, at its nature, pi is about circles. It’s actually a ratio, a comparison of two lengths. If you were to take any circle—tiny, middle-sized, or huge—and divide its circumference by its diameter, you get pi. So pi is actually what makes something look like a circle to us. It’s kind of magical, and we’ll celebrate that through the Hula-Hoop contest.

We’re also planning to do some fun things in the evening with the circle that everybody loves: a pizza pie. We’ll have ways to play with it mathematically, such as measuring, and, then, of course, people can eat the pizza.

What is the most satisfying part of what you do?

By far, it’s when I'm in the museum and I see the look of delight on people's faces or hear somebody say, "That's so cool!" That's exactly the impression that we're trying to convey, and you just don't normally see that kind of reaction to mathematics. Once, I was sitting outside the museum, and I saw a child run up to the front door ahead of her parents, jumping up and down excitedly and saying "It's MoMath! We're here! Come on!" What a beautiful thing that was.

We have a lot of stories of parents bringing in one child who likes math and another who doesn’t, and then not being able to leave because the non-math-loving child wants to stay. I also love talking to people from other states, who often tell me this is the only place they want to visit in New York—which is really saying something because there are so many absolutely phenomenal museums here.

What else is on the horizon?

We have a program that allows us to bring a prominent research mathematician to be with us for a year at MoMath. In our second year, Dartmouth’s Peter Winkler, whose specialty is puzzles, will continue to host puzzle workshops and other events from March through August. We’re also very happy to be bringing in Steve Strogatz—a very well-known New York Times blogger and prominent math popularizer—for a yearlong series starting in September.

We’ve also become an international tourist destination, and we’re part of the international communications world of people who run math museums and do math outreach. This September, we are co-convening an international conference in Paris with the Institut Henri Poincaré (IHP) and a group from Germany called IMAGINARY.

With MoMath being such a popular tourist destination, what do you hope people walk away with after visiting?

It depends what they walk in with. I hope that people who love math are happy to find some deep mathematics embedded in our exhibits and leave having experienced some new moments of delight.

If people disliked or feared mathematics before, I hope they leave realizing that math covers a much broader landscape—and that it’s more compelling and fun—than they thought.

For more info, visit momath.org

Share this unique math-based museum with friends and family.